What’s So Special About Alaska’s Special Areas?

And actually, what are Special Areas? Here’s a breakdown of the history of these life-giving zones in Alaska’s Western Arctic, and how Audubon Alaska staff helped to protect some of the most unique places on the planet.

Wildlife in Teshekpuk Lake Special Area (Photo: Kiliii Yuyan)

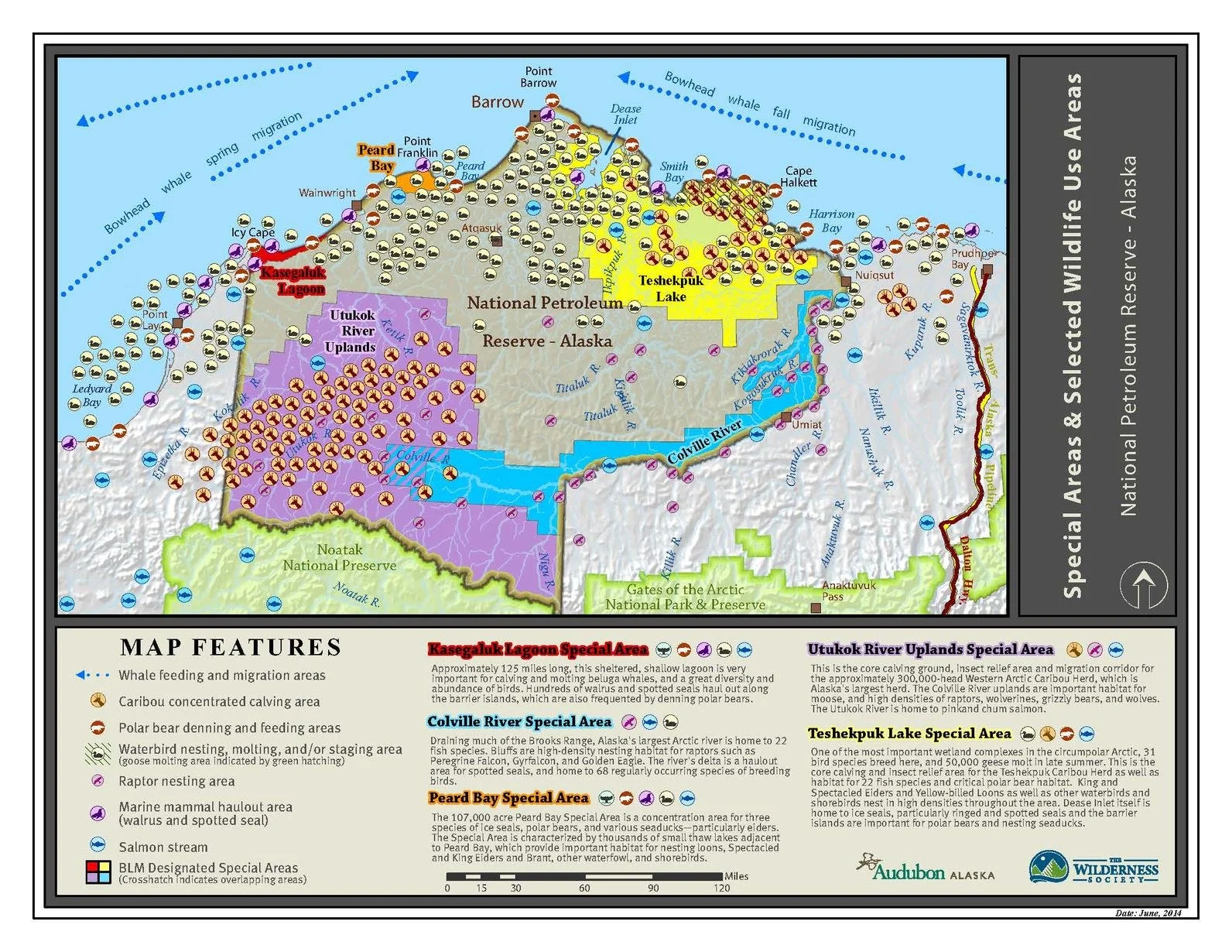

On September 6, 2023, the Department of the Interior under the Biden administration made three historic announcements concerning America's Arctic. One was a conservation rule that would strengthen protections for the designated Special Areas of the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska (NPR–A) of the Western Arctic, and establish a process for creating additional ones.

This surely earned praise from Alaska conservationists, but it’d be hard to find folks outside of the state—or outside of the Alaska environmental scene for that matter—where Special Areas prompt any reaction at all. That’s because they are unique to Alaska...and a little complicated.

Five Special Areas cover more than 13 million acres within the 23-million-acre NPR–A—the nation’s largest tract of public land. This landscape supports some of the most important avian habitat on the planet and is culturally irreplaceable for numerous communities across northern and western Alaska. The Reserve is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), though Alaska Native peoples have occupied these lands since time immemorial.

So what are Special Areas? How did they come to be? And what’s so special about them? The answers, of course, teems with political policy and Alaska history. And to help, we’ve rounded up the Mount Rushmore of Alaska conservation and policy experts from Audubon Alaska’s past to explain.

What and Why are Special Areas?

Despite the unfortunate name of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, this region of Alaska's Western Arctic supports incredible bird and wildlife habitat. So why is it called this? Policy wonks, get excited. Everyone else, buckle up.

The designated Special Areas of the NPR–A have outstanding wildlife values for a range of species. (Photo: Melanie Smith)

National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska

“This all really tracks back to the original establishment of these petroleum reserves in 1923 under President Harding,” says Eric Myers, former Audubon Alaska policy director. “At that time, the Navy was transitioning from coal to oil.”

In the early 1900s, the federal government started establishing naval petroleum reserves on public land to sustain the Navy. In fact, the original name of the NPR–A was the Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4—or Pet 4.

“Later, in 1976, “Congress recognized that there were extraordinary surface values that warranted careful management as the exploration of these areas moved forward,” Myers says. Surface values refer to wildlife, water, recreational opportunities, and scenery. It also became clear that subsistence was a particularly important value unique to Alaska, which heightened the interest in safeguarding these surface values. Special Areas were starting to take shape.

“They are an oddity,” he says, “And they don't exist anywhere else.”

Also in 1976, Congress passed the Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act (NPRPA), which renamed the area National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska. It also changed management.

Dr. John Schoen, former senior scientist for Audubon Alaska, and Eric Myers, former Audubon Alaska policy director. (Photo: Audubon Alaska)

“Congress transferred the reserve from the Navy to the Department of Interior and directed the Secretary of Interior to provide ‘maximum protection to areas of the reserve with significant subsistence, recreational, fish and wildlife, or historical or scenic value,’” says Dr. John Schoen, retired wildlife ecologist who spent 14 years as the senior scientist for Audubon Alaska.

Originally, there were three Special Areas—Teshekpuk Lake, the Utukok River Uplands, and Colville River. Kasegaluk Lagoon and Peard Bay came later to make five.

But Pat Pourchot—retired from the Department of the Interior as Special Assistant to the Secretary for Alaska Affairs wants to stress that “Special Areas are not synonymous with no oil and gas leases.” He says it’s because “whether right or wrong, that many people think of the reserve as an oil reserve.” Meaning Special Areas to this day still do not have maximum protection.

Stan Senner, former Audubon Alaska Executive Director, says it’s because because the NPRPA must be read carefully.

“They're supposed to provide maximum protection consistent with the purposes of the Act, including oil and gas exploration and presumably development,” he says. “The ‘Special Area’ is an attempt to draw a line around an area that has a number of these significant values and in theory, any oil and gas activities there, if allowed to go forward, needed to be done more carefully than might be done elsewhere. So it was a ‘special’ area in that sense.”

Why Each Special Area Needs Maximum Protection

Schoen says in his experience in the NPR–A, the Special Areas “have extraordinary value, ecological value for water, birds, and caribou and marine mammals and subsistence, to say nothing about the wilderness values or recreational values.” So let’s take a look at why each Special Area is just that.

Kasegaluk Lagoon Special Area and barrier islands. (Photo: Subhankar Banerjee)

Colville River Special Area—2.44 million acres

“The Colville River Special Area is the location of what is likely the highest-density raptor nesting area in the Circumpolar Arctic—Peregrine Falcons, Rough-legged Hawks, and Golden Eagles galore,” says Melanie Smith, former Director of Conservation Science for Audubon Alaska (and currently the Bird Migration Explorer Program Director at National Audubon Society). “Those species are long-distance migrants, so that connects this place to many, many other places far away and makes it part of the fabric of connected, protected, or unprotected areas that these species are relying on.”

Schoen agrees. “Probably nowhere else in the entire circumpolar Arctic can one find such a diversity and density of nesting raptors,” he says.

The Colville is the largest river in Arctic Alaska and stretches across the southeastern border of the NPR–A. The river delta supports 68 regularly breeding bird species and 22 overwintering fish species and is a major haulout site for spotted seals. The river corridor is used by caribou, moose, wolf, and grizzly bear.

Kasegaluk Lagoon Special Area—97,000 acres

Kasegaluk Lagoon is a highly productive shallow coastal lagoon and barrier island system spanning 125 miles of the Chukchi Sea coast. Approximately 40 miles of the lagoon are within the NPR–A, between Icy Cape and the community of Wainwright.

Pourchot says Kasegaluk Lagoon has, much like the other Special Areas, layered values. “It has migratory bird and resting areas in the lagoon and offshore of the lagoon, but it also has a lot of marine mammal values,” he says. Those include walrus and Beluga whale, and several species of ice seals. It’s also a denning and feeding habitat for polar bear.

This is also a globally significant Important Bird Area, established for having the highest diversity and abundance of birds of any lagoon system in Arctic Alaska. This area provides a migration and staging corridor likely used by the entire breeding population of King Eiders in Western North America, a nesting colony of approximately 500 Common Eiders, and a migration area for as many as half of the Pacific Brant population. It’s also a high-density waterbird nesting habitat for threatened Spectacled Eiders and multiple Alaska WatchList and other species, including Pacific Brant, Long-tailed Ducks, Northern Pintails, Pacific Loons, Red-throated Loons, a variety of shorebirds, and Greater White-fronted Geese.

Finally, it’s “important to local subsistence users,” Pourchot says. The coastal area along the Chukchi Sea from Icy Cape to Point Franklin, including Kasegaluk Lagoon, is valuable to the Wainwright as a subsistence harvest area for marine mammals and birds.

Peard Bay Special Area—107,000 acres

Schoen says this Special Area provides vital habitat for several marine mammals and is an important staging and migration area for shorebirds and waterfowl.

Peard Bay and the surrounding wetland complex is a concentration area for three species of ice seals and is important habitat for hauled-out walruses and polar bear denning and feeding. “Coastal denning areas are expected to be of increasing importance due to reduced availability and quality of pack ice denning habitat,” he says.

Snowy Owl chicks at Teshekpuk Lake Special Area. (Photo: Kiliii Yuyan)

This continentally significant Important Bird Area is crucial to nesting Spectacled Eiders and provides high-density nesting habitat for multiple Watchlist species. Think Arctic Terns, Red-throated Loons, Pacific Loons, King Eiders, Long-tailed Ducks, Sabine’s Gull, Greater White-fronted Geese, and tons of shorebirds.

Teshekpuk Lake Special Area—3.65 million acres

Teshekpuk Lake is the largest lake in Alaska’s Arctic and the third largest in the state. This internationally recognized area encompasses wetlands, coastlines, barrier islands, and the Ikpikpuk River Delta. Birds from this region disperse along all four major flyways.

To Senner, “it’s one of the most important areas for waterbird nesting, molting, and migration anywhere in the Circumpolar Arctic.” This sensitive area provides habitat for tens of thousands of molting geese, more than 60,000 individuals. Senner says it’s particularly Brant (about 20% of the population) coming from Canada, Russia, and the Yukon Delta in Alaska and heading north to molt at Teshekpuk Lake. Senner also says that “80% of the Yellow-billed Loons nesting in Alaska are found within the National Petroleum Reserve, and that's primarily the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area.”

“T-Lake” is also a high-density waterbird nesting habitat for species like Arctic Terns, Canada Geese, King Eiders, Long-tailed Ducks, Northern Pintails, Pacific Loons, Red-throated Loons, Sabine’s Gulls, Tundra Swans, Greater White-fronted Geese, and shorebirds.

Once again, the area is a critical denning and feeding habitat for polar bear. Schoen says barrier islands provide critical habitat features essential for the conservation of the species, including denning, refuge from human disturbance, access to maternal dens and feeding habitat, and travel along the coast. It’s also a calving and insect relief area for the 40,000-head Teshekpuk Caribou Herd (TCH)—a critical, year-round subsistence resource that provides roughly 60%, about 5,000 animals, of the caribou harvested by communities of the North Slope.

Caribou on Pik Dunes at the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area. (Photo: Subhankar Banerjee)

Finally, T-Lake is home to Pik Dunes, which previously was recommended for inclusion in the National Park Service’s Registry of National Natural Landmarks. This small area provides insect-relief habitat for caribou, has rare or uncommon plants endemic to the area, and is used by Yellow-billed Loons and other water- and shorebirds. All this plus the scenic, recreational, and cultural values of the site.

Utukok Uplands Special Area—7.1 million acres

Caribou crossing the Utukok River in the Western Arctic. (Photo: Subhankar Banerjee)

For the Utukok Uplands, Schoen wants to keep us on caribou. That's because this area is a critical calving and insect relief area for the 164,000-head Western Arctic Caribou Herd—one of the two largest caribou herds in Alaska. He says caribou in those numbers are a keystone species, providing resources for scavengers, birds and mammals, predators, and people.

“There have been about 15,000 caribou harvested each year, mostly by Alaska Natives,” he says. “There are 40 Native villages that depend on that caribou herd. So that herd is really important to the culture and subsistence values of many villages and many Native people.”

The Utukok Uplands is also valuable to grizzly bears, wolves, and wolverine—all iconic Alaskan species. “The wilderness values there match any in the world,” he says.

What Is a Rulemaking and How Does This Rule Stack Up?

Rulemaking is the process federal agencies use to make new regulations, though it’s not quite a law. (Those familiar may lean on the never-ending Roadless Rule saga in the Tongass National Forest as an example.)

“There are laws that Congress enacts and then there are regulations that an agency will put into place to carry out the policy will of Congress,” Senner says. “It's the rulebook that the agency will follow going forward.” Schoen is quick to add, “It’s like putting a blueprint together for building a house. This is how we're going to manage this place.”

Again, part of the aforementioned September 6 announcements initiated a new conservation rule that would strengthen protections for all 13 million acres of designated Special Areas and establish a process for creating additional Special Areas within the region “consistent with its duties under the NPRPA, Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), and other authorities.”

The proposal of this rule is celebrated by conservationists. Recognition that Special Areas are important at the federal level is a major plus (especially considering the actions of the last administration). But many agree a few things need to be addressed.

For example: “BLM is going to facilitate access to subsistence resources, but they don't spell out what that means,” Senner says. Does that mean building roads for subsistence access? Roads can be problematic. Plus there are restrictions on infrastructure in some of the Special Areas, but then exceptions can be made if the infrastructure will primarily serve a community. “There's just a lot of really gray, fuzzy kind of things in there that ideally need to get tightened up a little bit,” he says.

And currently, the aforementioned Pik Dunes in the Teshespuk Lake Special Area may have “sand and gravel mining authorized on a case-by-case basis.” But Senner sees a fix. “This rule doesn’t change that but that's something that they could address in the future in a new IAP, but right now, there it is.”

Freeze. That’s a new term. IAP means Integrated Activity Plan, which also has a lot to do with this. According to the BLM, the proposed rule would raise the bar for development throughout the NPR–A by establishing clear guidelines that are consistent with provisions of the current NPR–A Integrated Activity Plan which was put in place in 2022. It effectively reversed the Trump administration’s IAP that sought to expand oil and gas leasing and development in the NPR-A and reduce protections for the Special Areas.

Finally, it’s important to remember the proposed rule would establish a framework and guidance for both conservation—and to some extent, development—in the NPR–A. The rule would not affect currently authorized oil and gas operations. “It is a reality that there are significant areas already under lease,” Senner says. “and these new rules won't apply to them.”

Caribou approaching a pipeline in the Western Arctic. (Photo: Kiliii Yuyan)

What Do Special Areas Need Protection From?

In recent years, large oil and gas projects, including the Willow Master Development Plan, have been approved inside the NPR–A. Development deals another blow to the Western Arctic. And human disturbance plus loss of habitat from road and pipeline construction, aircraft, and activity could be detrimental to the area’s sensitive wildlife populations.

These “cumulative effects could be really damaging,” says Schoen. But what bothers him most is the lack of a comprehensive conservation strategy for the North Slope—the only Arctic ecosystem in the United States.

John Schoen, Stan Senner, and Pat Pourchot in 2009. (Photo: Audubon Alaska)

“Before we commit so much land to development, it seems like we ought to have some kind of comprehensive strategy,” he says. “It seems irresponsible for the leadership of our country and the state of Alaska to just keep developing, developing, developing without some big landscape vision of how we want to balance resource development…along with conservation.”

Then, of course, there’s climate change, “which is warming the Arctic four times faster than anywhere else on the globe,” says Myers. Increased carbon emissions resulting from exploration, development, and extraction of oil from the ground add to this.

Schoen says the combination of this warming and emissions with the changing extent and timing of sea ice will affect the distribution and abundance of marine and terrestrial plants and animals. Walrus haulouts and polar bear denning will be impacted. Caribou will lose tundra habitat to shrubs, have less insect-relief habitat, and more.

“Combined with the additional stressors of widespread oil and gas development across Alaska’s fragile tundra and wetland habitats, these changes will likely have significant and compounding impacts on wildlife and fish habitats and populations and the subsistence uses of these important resources across Alaska’s North Slope,” he says.

Schoen stresses the effects of increased carbon emissions on the Western Arctic should be better calculated and evaluated in terms of their contribution to climate change. Because, he says, many climate scientists believe we are at a tipping point in our ability to slow or halt the accelerated climate warming that is now occurring.

“Without an adequate scientific understanding of the cumulative effects of development compounded by climate change,” he says, “It is unlikely that mitigation of impacts to this complex ecosystem will be effective.”

The People Involved And Public Involvement

We’ve been talking about public land, so where does the public—and the residents—fit into all this?

Communities like Utqiagvik Anaktuvuk Pass, Atqasuk, Nuiqsut, Point Lay, and Wainwright harvest nearly all of their subsistence resources from the NPR-A. (Photo: Lauren Cusimano)

As mentioned, more than 40 communities, especially Anaktuvuk Pass, Atqasuk, Nuiqsut, Point Lay, Utqiagvik, and Wainwright harvest nearly all of their subsistence resources from the NPR-A according to the BLM. This includes caribou, moose, mammals, fish, waterfowl, upland game birds, and vegetation.

What’s more, the Reserve holds cultural resources. The BLM states that nearly 2,000 sites have been identified on less than the 3% of the NPR-A that has been surveyed. There are 925 documented Traditional Land Use Inventory sites, including landmarks, traditional land use sites, travel routes, and other places of cultural importance to the North Slope Iñupiat. “These sites have ongoing spiritual and cultural importance to residents of the North Slope,” reads the BLM language for the proposed rule.

Then there are the recreators in the NPR-A seeking classic Alaskan activities like backpacking, boating, hunting, fishing, and off-highway vehicle use on what is arguably the most remote landscape in the United States.

Do all these inhabitants and visitors have a say on this proposed rule? They do.

As Pat Pourchot puts it, “There are rules for the rulemaking.” It requires publication in the Federal Register, a review period, a public comment period, and local and/or national hearings. The process then goes into draft rulemaking, then final rulemaking, then final publication. “So it's not an arbitrary process for adopting regulation,” he says.

Most recently, the public was invited to comment for 90 days on this rulemaking from September 8 to December 7, 2023.

Could There Be More Special Areas Someday?

According to the BLM, this proposed rule would also, “for the first time, provide standards and procedures for designating and amending Special Areas.”

Red Phalarope at Teshekpuk Lake Special Area—which might be an obvious region to expand with this new rule. (Photo: Gerrit Vyn)

Every five years, the BLM would take a hard look at the NPR-A to designate new Special Areas or update existing Special Areas by “expanding their boundaries, recognizing the presence of additional significant resource values, or requiring additional measures to assure maximum protection of significant resource values.” That last one we definitely want. The five-year timeframe was established based on how “rapidly conditions across the Arctic are changing,” states the BLM language.

So, what spots are on deck?

Pourchot says a standard practice is more the expansion of current Special Areas, as opposed to new, isolated Special Areas. For example, based on important caribou calving area in the Utokok Uplands, this Special Area could be expanded down to the Brooks Range boundary and the western boundary. And similar things could be said for the other four Special Areas. “There's a lot of justification for expanding some of these special areas based on their values,” he says.

Senner has recommended in various public comments that the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area be expanded west to the community of Atqasuk. “That'd be an obvious one,” he says. Senner is also quick to mention the Audubon dream of closing the gap between Kasegaluk Lagoon and Utokok Uplands by adding to the Special Areas or creating a wilderness designation, what Melanie Smith refers to as a connectivity corridor.

Melanie Smith joined Audubon Alaska in 2008 and set to work as a Spatial Ecologist on geospatial analysis and wildlife ecology for key bird and mammal habitat. (Photo: Audubon Alaska)

“So you would have the sweep of the whole North Slope from the Brooks Range, which a lot of is protected in the Noatak Preserve and other areas, all the way down through the Utokok Uplands, all the way out to the coast at Kaseluck Lagoon and Peard Bay,” Senner says. “I think there's wildlife justification for that, but unquestionably there's wilderness justification for it.”

But Eric Myers wants to remind us there are multiple Important Bird Areas within the NPR–A, but not necessarily in the Special Areas, that have been identified by Audubon and also warrant special consideration. In fact, “there's not a whole lot of real estate that doesn't have exceptional, extraordinary values up there,” he says.

Audubon Alaska’s Part in This

Not to brag, but Audubon Alaska has had a lot to do with how the NPR–A looks today.

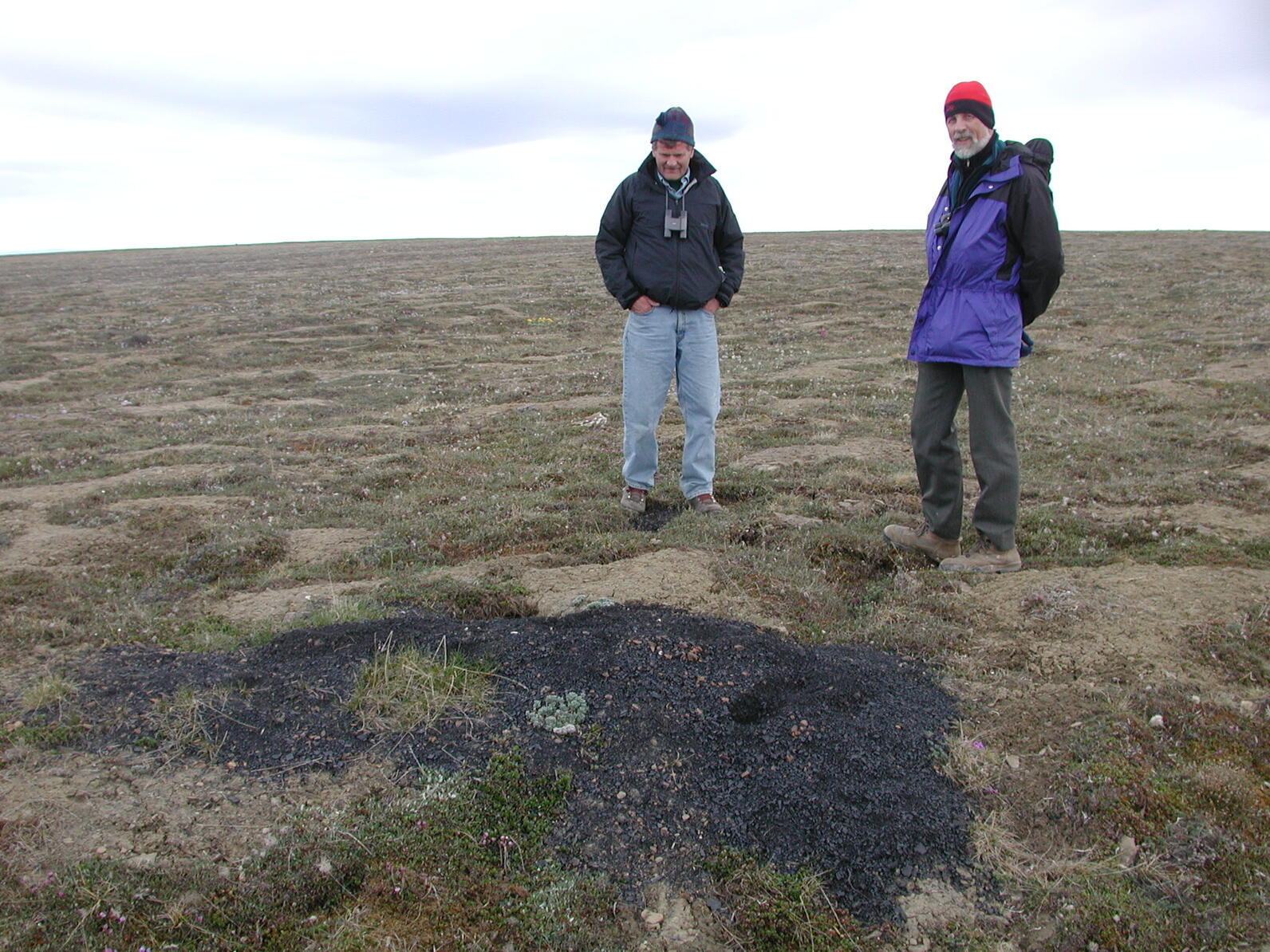

John Schoen and Jim Owens, then with the Brainerd Foundation, viewing a marmot den dug into a coal seam in the Utukok River Uplands Special Area. (Photo: Tim Greyhavens/Wilburforce Foundation)

Stan Senner says we can thank Audubon and others who have labored for 25 years for a lot of the protections in place and what’s happening now with the proposed rule. “This has been a team effort, right from the very start,” he says. “I think it's absolutely fair to say none of this would be happening without Audubon's efforts.”

For a timeline: John Schoen first addressed NPR–A issues in 1998 about plans for development around Teshekpuk Lake as the senior scientist for Audubon Alaska. Stan Senner came on in 1999 as Executive Director. Melanie Smith joined in 2008 and set to work as a Spatial Ecologist on geospatial analysis and wildlife ecology for key bird and mammal habitat. Eric Myers came on in 2010, tackling all the legislative fun as Policy Director.

In short, this team, plus more on the Washington, D.C. side like Pourchot, conducted a resource assessment of the Western Arctic and a strategy for balancing resource development with the conservation of areas with high-value habitats for waterfowl, shorebirds, and birds of prey, as well as caribou, polar bears, beluga whales, and ice seals. This was not only done for the wildlife but for the fact that these species are important subsistence resources to the residents of northwestern Alaska.

There were also many partners along the way—The Wilderness Society, Alaska Wilderness League, and Earthjustice to name a few—as well as key early funders that sustained support over the last two decades, including the 444S, Brainerd, Campion, Hewlett, and Wilburforce foundations. There was also the American Conservation Association and the Beatrice Fox Auerbach Foundation at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving. The team would also like to acknowledge the primarily Native Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group that has been vigilant in encouraging protection for caribou habitat.

Pourchot can confirm the impact all this made on the Western Arctic.

“When I was with the Secretary's Office and working on the IAP from the Interior Department, it was Melanie and Eric's maps and John’s input in those later years that directly set the boundaries of some of those Special Areas like Utukok Uplands and Teshekpuk Lake,” he says. “I felt like that was the most valuable and important resource input that Interior was getting on setting the boundaries.”

Myers also sees the continuous effect of these efforts. “When you take the long view, and you realize that nobody was talking about the NPR–A in the terms that are being discussed now 30 years ago,” he says. “The needle has been moved markedly.”

And this leads us to our final question for the NPR–A dream team.

When Can We Rest?

Senner says, despite being thrilled over this fall’s rulemaking announcement, he knows the work Audubon Alaska has done for a quarter century is still not enough. “And it's definitely not the ultimate solution. And even if we had the ultimate solution, we'd see the delegation trying to undo the ultimate solution one way or another,” he says. “But we should be proud of how far we've come, and this rule is a manifestation of that.”

Oil development in Alaska's Western Arctic. (Photo: Kiliii Yuyan)

Senner is referring to the fact that the next presidential administration could target the Arctic for oil and gas projects and development. Myers agrees. He says what’s happening with the NPR–A now is valuable in the hands of the right administration, “but we're still on very thin ice as far as the entire Reserve is concerned.” A change in administration could make everyone go back to square one, and that threat might never go away.

“I suppose coming to terms with that is the hardest part of all,” he says. “Until there's a national park or national monument or something that has more durability, that you can transcend one administration the next, it's hard to get too worked up.”

Smith understands this well, saying, “This is why certain long-term campaigns, you can't walk away…we have to stick it out.” But, she says, without everything Audubon has done, the Western Arctic would probably look significantly different. “We've made so much progress really.”

And there’s still a best-case scenario out there. Congressional action could happen to put more enduring, possibly permanent, designations on these Special Areas and beyond. “Recognizing that what Congress does can always be undone,” Senner says, “that's as permanent as we can get.”

Myers is looking further than that, explaining that a real energy transition is what’s needed, something that will hinder the interest in development and petroleum in the Reserve and the Arctic. “I think oil and gas development has to be addressed comprehensively if we're going to see the Arctic protected,” he says.

As of November 9, a federal judge in Alaska upheld the Biden administration’s approval of the Willow Master Development Plan on the North Slope—one of the largest oil developments on federal land in decades.

So, can we rest? Probably not.